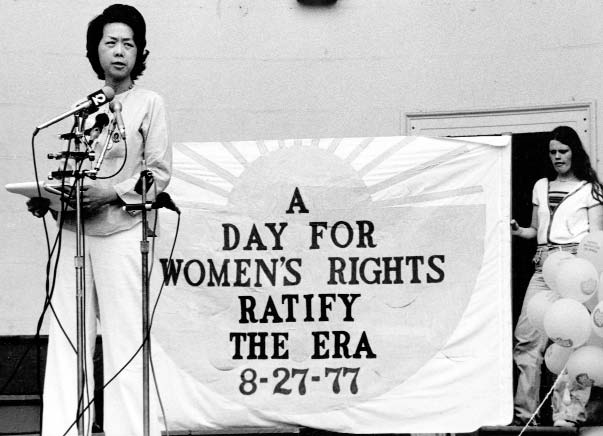

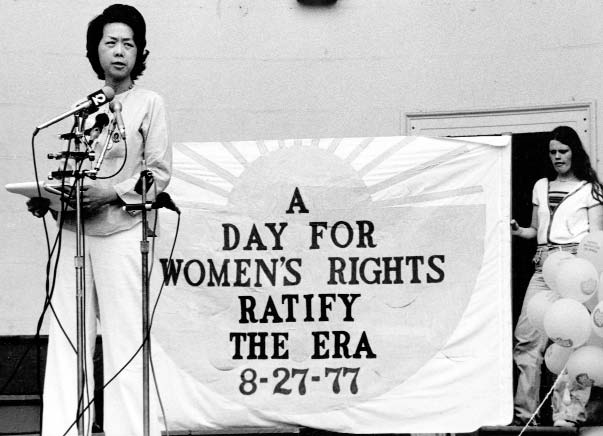

Goldie Chu

Date: Aug 27, 1977

Caption: Activist Goldie Chu participated in community control of schools in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She continued to serve as a member of the governing board of her local district, which helped launch her into a lifetime of activism.

Please note: This is work in progress. Please keep that in mind as you read. We are sharing this work in progress because these materials are relevant to discussions of school governance underway right now in New York. Please share your feedback at [email protected] and check back for updated versions soon.

In addition to the community control districts in Harlem and Ocean Hill-Brownsville, there was one in Manhattan’s Two Bridges neighborhood on the Lower East Side. Two Bridges differed from those in Harlem and Ocean Hill-Brownsville in important ways. Policymakers and white borough residents had created segregated neighborhoods and school districts throughout the twentieth century. In Harlem and Ocean Hill-Brownsville, this meant that the student body was exclusively Black and Puerto Rican. While similar policies shaped the neighborhood patterns within Two Bridges, the schools there served a more varied student body, including Chinese American, Puerto Rican, African American, and white families. Two Bridges had a more diverse student body than the other experimental school districts.

One of the leading figures in the Two Bridges community control district was Goldie Chu. Chu was a mother of five who worked across racial, ethnic, and class lines to empower working-class families in the neighborhood. Born in Hawai’i, Chu and her family moved to the Chinatown neighborhood in New York when she was 16. She became active in community politics and organizations at a young age, and she began working as a teacher’s assistant in a school whose student population was over 70 percent Chinese American. While in that job, she was recruited by the women-led Parents Development Program, (PDP) which sought to increase parent participation in local government. Chu later became the group’s leader and a member of the governing board of the Two Bridges community control district.

Chu faced numerous barriers and challenges in her organizing. For one, her husband held conservative beliefs about the roles of women within society, and, therefore, she hid her organizing and activism from him. Moreover, some Chinese Americans living in the neighborhood questioned her ability to represent the Chinese American community because she was a second-generation Chinese American and “sp[oke] very little Chinese and c[ould not] read and write the language.”1 Nevertheless, Chu worked actively across racial, ethnic, and class lines. Local school boards were previously dominated by middle-class families (across racial and ethnic groups) who thought that schools should assimilate students into what they thought of as mainstream American culture. Chu and her allies instead advocated for schools to recognize, honor, and leverage students’ racial and ethnic identities to help their learning.

Community control in a diverse district brought its own challenges. For instance, in one school board meeting, Chinese American families argued for a bilingual education program that would help Chinese American students learn English. Many of the Puerto Rican families in that meeting worried that the establishment of such courses would leave the school unable to support the bilingual program they desired for their Spanish-speaking students. Meanwhile, African American families at the meeting expressed their concerns that so much focus on bilingual education would mean that not enough attention would be paid to African and African American heritage within the schools. The parents at the meeting eventually agreed to create “a series of cultural programs” in which “all children w[ould] study everyone’s culture.”2

Goldie Chu also became an example of how participation in community control helped launch some New Yorkers into advocacy in other spaces. Chu became a leader in the feminist movement of the 1970s and challenged stereotypes of Asian American women. In one interview, Chu recalled someone telling her that they didn’t know Chu was “a militant feminist,” to which Chu responded with a laugh, saying, “what is a militant feminist supposed to look like?” She commented that many regarded Asian American women “as passive and quiet… Others tend to sweep by us and think they can get away with it. I may be traditional in manners but not traditional in fighting for change in the community where there is so much to do.”3

-

Maia S. Merin, “The ‘Other’ Community Control: The Two Bridges Demonstration District and the Challenges of School Reform, 1965-1975 (PhD diss., New York University, 2015), 142. ↩︎

-

Merin, “The ‘Other’ Community Control,” 2. ↩︎

-

“Asian American Women Nurture a Growing Consciousness and Activism in Chinatown,” The New York Times, November 14, 1977. ↩︎

Categories: K-12 organizing, Manhattan, parent activism, community activism

Tags: Asian American people, self-determination, multiracial organizing, democracy, organizing, women's activism, photography, imagery, and visual representation"

This item is part of "The Push for Community Control" in "Who Governs Schools?"

Item Details

Date: Aug 27, 1977

Creator: Corky Lee

Source: Laguardia and Wagner Archives

Copyright: Under copyright

How to cite: “Goldie Chu,” Corky Lee, in New York City Civil Rights History Project, Accessed: [Month Day, Year], https://nyccivilrightshistory.org/gallery/goldie-chu.

Questions to Consider

- How did the community control district on the Lower East Side, called Two Bridges, differ from those in East Harlem and Brooklyn?

- What challenges did Goldie Chu face in her activism? How did she respond to them?

- How did participating in the community control district impact Goldie Chu’s later work?

- How does this photograph of activist Goldie Chu compare to other portraits and photographs of activists on this site, like William Maxwell and Black and Latina Women?

References

How to Print this Page

- Press Ctrl + P or Cmd + P to open the print dialogue window.

- Under settings, choose "display headers and footers" if you want to print page numbers and the web address.

- Embedded PDF files will not print as part of the page. For best printing results, download the PDF and print from Adobe Reader or Preview.