You are here:

The Educational Needs of the Puerto Rican Child, excerpts

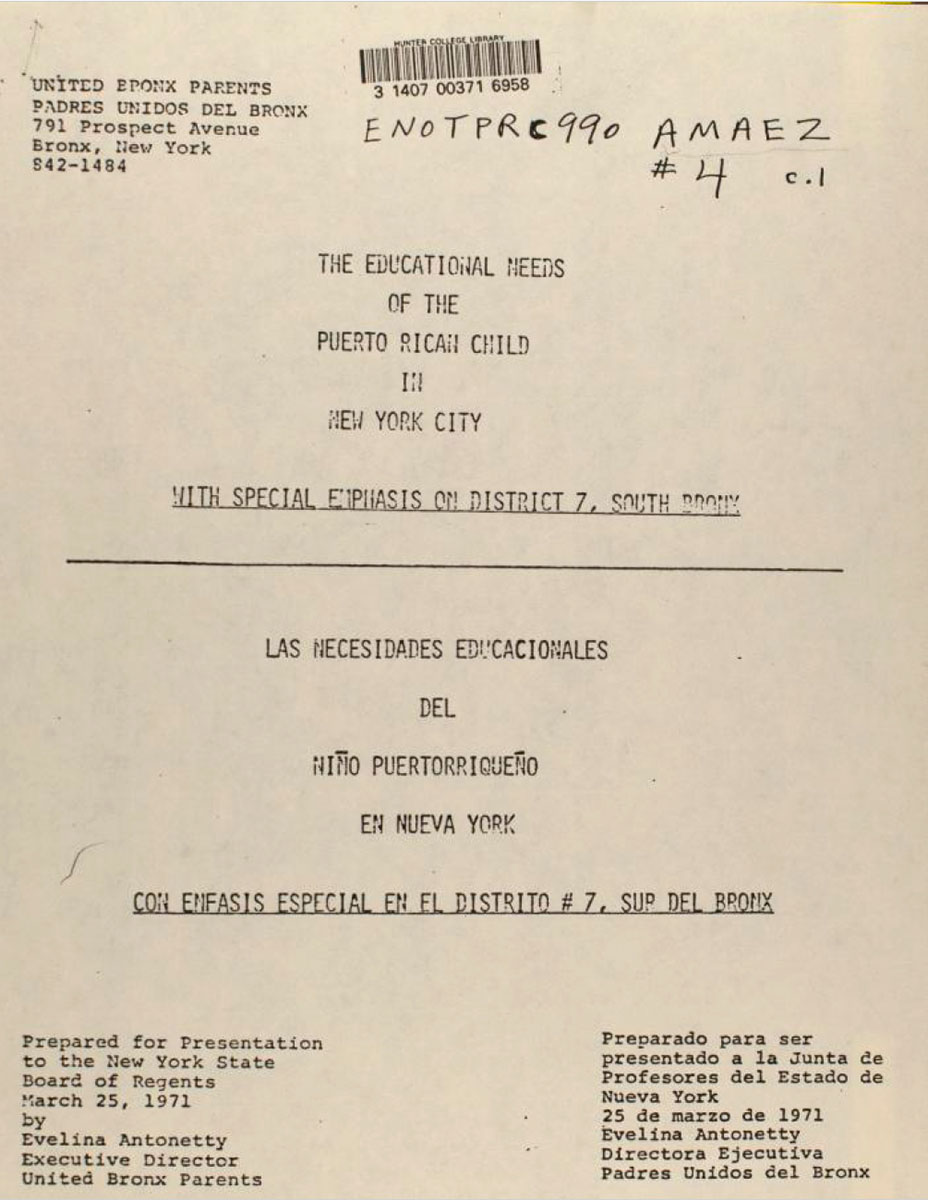

Date: Mar 25, 1971

Caption: United Bronx Parents organized parents in the South Bronx. Many members of the organization were Puerto Rican and Black New Yorkers whose children attended local public schools and were concerned about the quality of education they received there.

In 1970, about one quarter of all New York City public school students were Puerto Rican. And in some parts of the city, like the South Bronx, that proportion was much higher, around 65 percent.1 Many Puerto Rican students spoke Spanish at home, but the local public schools operated almost exclusively in English.

United Bronx Parents organized parents in the South Bronx to fight for better schools for their children. UBP director Evelina López Antonetty came to New York from Puerto Rico as a child and later raised her family in the South Bronx. Antonetty presented this report to New York State education officials. In it she criticized New York City schools and explained what steps the schools could take to make education more just for Puerto Rican students.

Testing was one area of concern in the report. Labeling Puerto Rican students as disabled had a long history in New York City. In 1935, the Board of Education sponsored a study of Puerto Rican students at one school in East Harlem. Students were given two kinds of intelligence tests. These tests - as Puerto Rican leaders and their allies pointed out at the time - could not be accurate measures of students’ intelligence. They were given only in English and they included many cultural references that were not familiar to most Puerto Rican students. Nevertheless, the Board of Education and its representatives spoke about the “subnormal Puerto Rican child” and characterized Puerto Rican boys and girls as threats to New York schools and the nation.2

Racist and ableist treatment of Puerto Rican children continued in New York schools, and organizations like United Bronx Parents worked hard to challenge them.

Lana Dee Povitz, Stirrings: How Activist New Yorkers United a Movement for Food Justice (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 266 note 30. ↩︎

Lorrin Thomas, Puerto Rican Citizen: History and Political Identity in Twentieth Century New York City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 85-88. ↩︎

Categories: Bronx, K-12 organizing, parent activism, community activism

Tags: Spanish language, bilingual education, Latinx people, Black people, women's activism, disability labels, teacher quality

This item is part of "Evelina López Antonetty and United Bronx Parents/Padres Unidos del Bronx" in "Black and Latina Women’s Educational Activism"

Item Details

Date: Mar 25, 1971

Creator: United Bronx Parents/Padres Unidos del Bronx

Source: Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Library & Archive

Copyright: Used with permission. Courtesy of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College.

How to cite: “The Educational Needs of the Puerto Rican Child, excerpts,” United Bronx Parents/Padres Unidos del Bronx, in New York City Civil Rights History Project, Accessed: [Month Day, Year], https://nyccivilrightshistory.org/gallery/educational-needs-of-the-puerto-rican-child.

Questions to Consider

- How is this report and its description of schooling for Puerto Rican students in the South Bronx in the 1970s similar to or different from Toni Cade Bambara’s description of Puerto Rican students going to school in Harlem in the 1940s? What seems to have continued? What seems to have changed?

- To whom was this report directed? How did United Bronx Parents make their argument? How did they use language to convince their audience?

- What do you think of their proposed changes in education, listed on p. 7 and 8? Are these changes still needed or relevant today?

References

How to Print this Page

- Press Ctrl + P or Cmd + P to open the print dialogue window.

- Under settings, choose "display headers and footers" if you want to print page numbers and the web address.

- Embedded PDF files will not print as part of the page. For best printing results, download the PDF and print from Adobe Reader or Preview.