You are here:

Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot, excerpt

Date: Jul 18, 1936

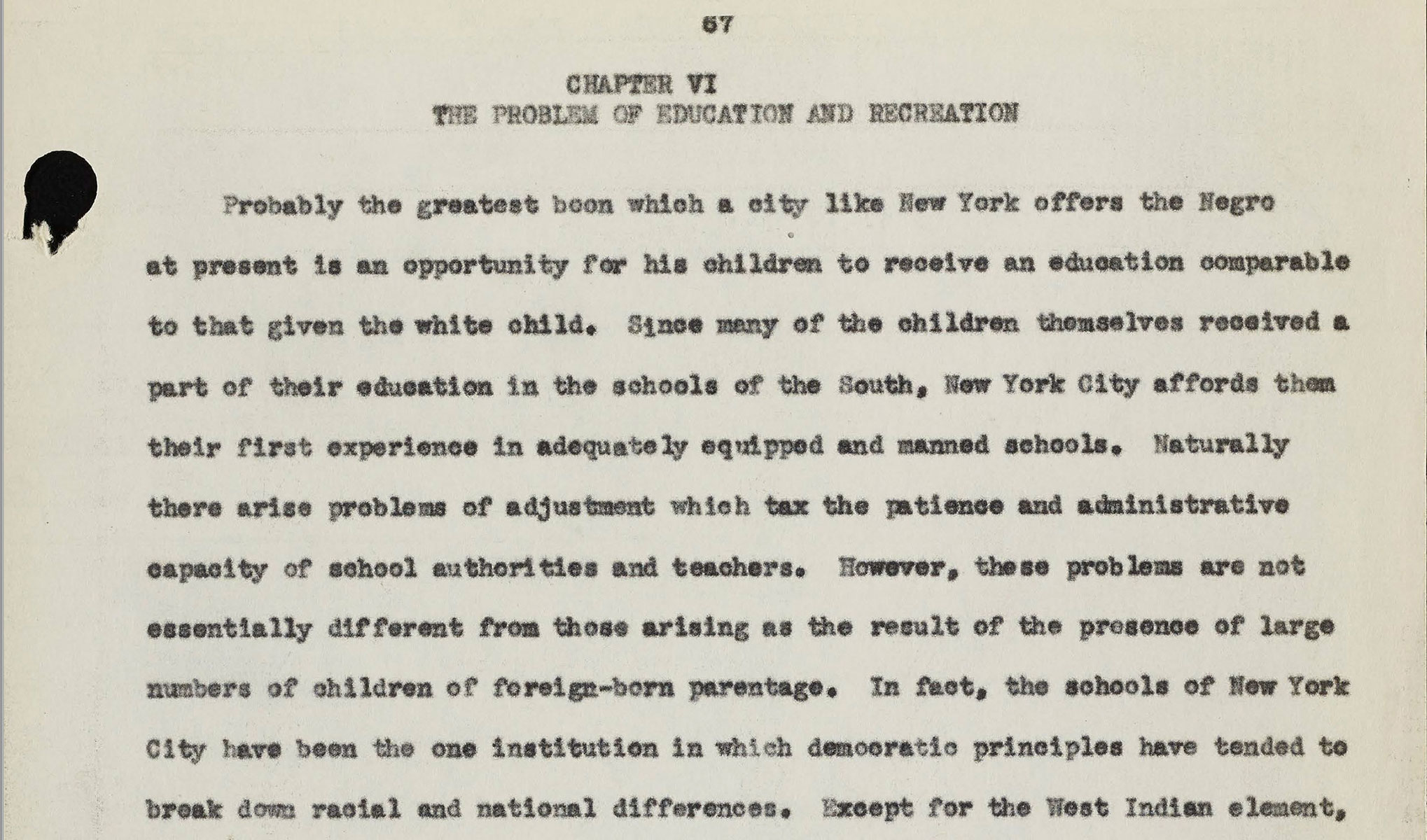

Caption: Mayor LaGuardia formed the LaGuardia Commission in the aftermath of the 1935 “Harlem Riot” to identify the event’s root causes and determine possible solutions. One chapter of the report, shown here, focused on education.

On March 19, 1935, rumors spread through Harlem that police had beaten a young man to death after they arrested him for allegedly stealing a knife from a local store. As New York Police Department officers regularly used violence in policing the neighborhood, the rumor was believable, even if it was not in fact true. Nevertheless, the rumor sparked a revolt by community members concerned about policing and many other kinds of injustice due to racism and the impact of the Great Depression. The police responded to the uprising with violence, resulting in the death of three Black men, more than 100 arrests, and at least another 100 people injured.1

In the aftermath of the uprising, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia assembled a commission to investigate the causes of the events that night. The LaGuardia Commission included both Black and white researchers. Notable leaders like Countee Cullen, A. Phillip Randolph, and Franklin E. Frazier worked together to create the report. Eunice Hunton Carter was the only woman to serve on the committee, but played one of the most important roles in synthesizing the committee’s findings. A talented lawyer and social worker, Carter carried out much of the Commission’s work on the ground, listening to and writing down community members’ complaints and concerns, which she incorporated into the final report.2 Many of the report’s most powerful depictions of educational inequality came from Black women teachers working in Harlem’s schools. They testified at hearings conducted by the Commission, but they did not want to be named in the report. They feared losing their jobs because they spoke out.

The Commission identified many sources of Harlem residents’ frustrations. They noted the police brutality, racial discrimination in employment, poor quality yet expensive housing, and limited educational opportunities. These were key reasons for the volatile response to the rumor of murder.

After the Commission finished its work and prepared its report, Mayor LaGuardia decided not to publish it. He tried to keep its findings hidden, until the New York Amsterdam News printed it in its entirety. As the Amsterdam News made clear in their preface to the report, the mayor thought it was “too hot, too caustic, too critical, [and] too unfavorable.”3

This excerpt is the chapter of the report that analyzes “the problem of education and recreation.” It specifically looks at what decisions limited educational opportunities for Black students in Harlem, including the inequitable distribution of resources, academic tracking, and racism inside Harlem schools.

-

Cheryl Greenberg, “The Politics of Disorder: Reexamining Harlem’s Riots of 1935 and 1943,” Journal of Urban History 18, no. 4 (August 1992): 395-419. To learn more about living and working conditions in Harlem in the 1920s, see Shannon King, Whose Harlem is This Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism during the New Negro Era (New York: New York University Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

Stephen L. Carter, Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster (New York: Picador, 2018), 87-98. ↩︎

-

Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot, The Complete Report of Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot of March 19, 1935 (New York: Arno Press, 1969). ↩︎

Categories: Manhattan, K-12 organizing, teacher activism

Tags: policing and the criminal legal system, Black people, Latinx people, racist segregation, Harlem, employment

This item is part of "Lucile Spence and Teacher Activism" in "Black and Latina Women’s Educational Activism"

Item Details

Date: Jul 18, 1936

Source: Municipal Archives of the City of New York

Copyright: Public domain. Courtesy of the Municipal Archives of the City of New York.

How to cite: “Mayor LaGuardia’s Commission on the Harlem Riot, excerpt,” in New York City Civil Rights History Project, Accessed: [Month Day, Year], https://nyccivilrightshistory.org/gallery/harlem-riot-report.

Questions to Consider

- Based on the report, how would you describe the conditions in Harlem schools in the 1930s? How are those conditions influenced by segregation?

- Mayor LaGuardia tried to shield the findings of his own commission from the general public. Why do you think he did that? What would have been the consequences if he had been successful?

- In 1935, the Commission concluded that persistent police brutality, racial discrimination in the labor market, segregated housing, and unequal education had sparked what was called at the time a “riot.” How do the events of 1935 compare to more recent protests against police violence or other forms of injustice?

- Have the issues identified by the commission in 1935 been addressed today?

References

How to Print this Page

- Press Ctrl + P or Cmd + P to open the print dialogue window.

- Under settings, choose "display headers and footers" if you want to print page numbers and the web address.

- Embedded PDF files will not print as part of the page. For best printing results, download the PDF and print from Adobe Reader or Preview.