You are here:

Lucile Spence and Teacher Activism

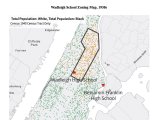

In the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, New York’s Black population grew dramatically. Black southerners arrived as part of the Great Migration, fleeing violence, poverty, and political oppression in the Jim Crow South. Black migrants from the Caribbean arrived in substantial numbers as well. There were more and more Black children in New York City’s schools. But there were very few Black teachers.1

Read More

New York City put many barriers in place to prevent Black teachers from getting jobs. Black teachers had less access to the college training needed to become a teacher. Those who already had the degrees and other qualifications faced a racist and ableist examination structure, one which disqualified teachers for their speech - if they had southern or non-native accents when speaking English - or their bodies, if they were judged overweight or otherwise disabled, in the eyes of the examiners.2

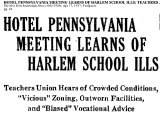

Many of the Black teachers who cleared these hurdles and did get hired as teachers worked in solidarity with one another, with white colleagues (many of whom were Jewish leftists) and with parents in their communities. Together they found a variety of ways to protest and seek equality for New York students.3

During the anti-communist “Red Scare” of the early 1940s through the 1950s, Black activist educators like Lucile Spence and her peers, and some of their white Jewish colleagues, were accused of membership in the Communist Party, which, if proven, would have led to their being fired from their teaching positions under New York law.[^4] Whether they were members of the party or not, Spence and her peers sought radical change in the US. They wanted to end the racism and poverty faced by many of their Black students in New York City.

-

Christina Collins, Ethnically Qualified: Race, Merit, and the Selection of Urban Teachers, 1920-1980 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

Collins, Ethnically Qualified; Diana D’Amico Pawlewicz, Blaming Teachers: Professionalization Policies and the Failure of Reform in American History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019); Jonna Perrillo, “Beyond ‘Progressive’ Reform: Bodies, Discipline, and the Construction of the Professional Teacher in Interwar America,” History of Education Quarterly 44, no. 3 (Autumn, 2004): 337-363; Kate Rousmaniere, “Those Who Can’t, Teach: The Disabling History of American Educators,” History of Education Quarterly 53, no. 1 (February 2013): 90-103. ↩︎

-

Clarence Taylor, “Harlem Schools and the New York City Teachers Union,” in Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community, ed. Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), https://harlemeducationhistory.library.columbia.edu/book/chapters/06/; Jonna Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩︎