Seeking Equity for Disabled Students

New York City has always provided education in exclusive and segregating ways, from the colonial period onward. For disabled children, exclusion and segregation have been common experiences. Sometimes education officials said this was justified by the need for specialized instruction. Other times, they made claims about some students not being fit for certain types of learning. Children with physical disabilities faced architectural barriers that made access to classrooms difficult or impossible.

Read More

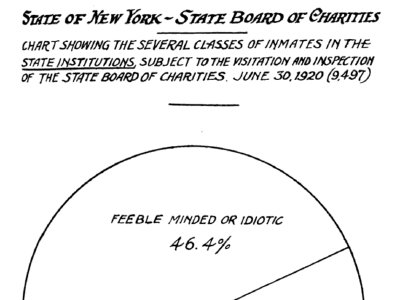

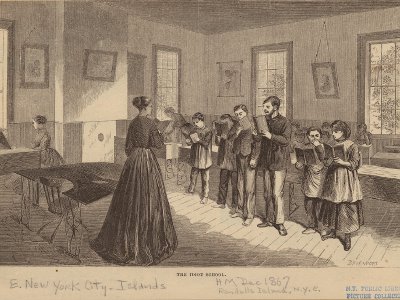

A wide variety of human differences that have been stigmatized throughout history are now gathered under the term “disabled.” Thus disability is extremely diverse as a social category. Both the category of disability and the exclusion of disabled children have been linked to race, citizenship, language, class, gender, and sexuality. A hierarchy among types of disability was also visible in the geography of the nineteenth century city: charitable schools for the blind and deaf were located in Manhattan, but a school for intellectually Disabled people sat on Randall’s Island in the East River, among hospitals, asylums, prisons, and orphanages housing society’s “undesirables.”

Advocates for children with disabilities have focused their efforts on building new programs or facilities for disabled children. They were motivated by a desire to help, but these new institutions (especially when they were underfunded), created problems of their own (and even horrors, as in the inhumane conditions at Willowbrook State School). Many educators, very few of whom were disabled themselves, sought to minimize students’ disabilities so they could fit in with the rest of society. For example, Deaf students were not allowed to use sign language to communicate in school settings even though sign language supported their language development and culture.

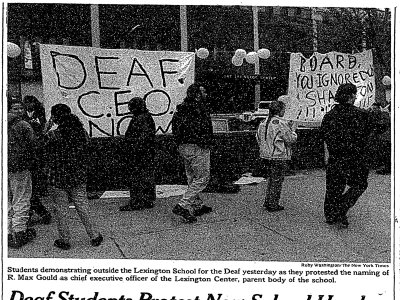

All of these problems and more prompted organizing by students, parents, and educators. Advocates used a wide range of strategies to fight for justice for Disabled students, including filing lawsuits, organizing direct-action protests, building community spaces, and creating art. Parents and advocates fought for equity in many different areas, including for access to learning opportunities, architectural access, and communication access. They also pushed against unfair or racist labeling that leads to greater segregation.

NYC’s educational landscape for disabled children looks very different than it did one hundred years ago, but some things are quite unchanged. Students understood to be outside of normal in some way see much less support, care, and opportunity than they deserve. Racial and class inequalities continue to shape what disability is and how people experience it.

Although old patterns of injustice continue, Disabled people, their parents, and those working in solidarity with them are shaping and pushing for their visions of equity and justice.

The Beginnings of Special Education

The earliest schools segregated disabled children in hopes they could attend school with nonDisabled students or fit in with society as adults.

View primary sources

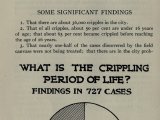

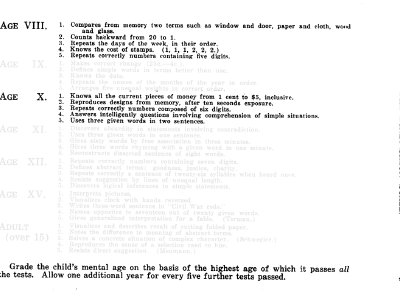

Tests, Labels, and Segregation in New York City

New intelligence tests were celebrated by the era’s eugenics movement and used to keep students out of public schools.

View primary sources

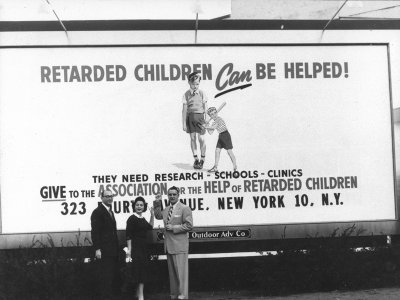

The Parents’ Movement for Deinstitutionalization and School Access

Parents in New York City organized for access to public education for their children, and more funding for care.

View primary sources

Fighting to Fit In: Physical Access

One of the most persistent problems for physically Disabled students seeking education is the lack of wheelchair accessible schools.

View primary sources