You are here:

The Push for Community Control

After years of frustration at how neighborhoods like Harlem were treated by the centralized Board of Education and the predominantly white teachers, principals, and school officials working there, despite decades of community protest, Black and Latinx New Yorkers and white people working in solidarity with them pushed for a change in how schools were governed in NYC.1 They wanted to be able to elect local representatives who would have real power over how schools worked, who worked in them, and what students learned. Activists who had been fighting for desegregation were frustrated at how long segregation was lasting and how little the Board of Education had been willing to challenge it - even after massive protests like the NYC school boycotts. If the system was going to stay segregated, they argued, then at least communities of color should have more power in running schools.

Read More

Local education advocates helped pressure the New York City and State governments to experiment with community control of some New York City schools. The city created three “demonstration districts” where parents and community members would have democratic control over their schools. Parents and community residents could elect local school boards to make decisions about who would teach in their schools and how the schools would run. These districts were in Ocean-Hill Brownsville in Brooklyn, and in East Harlem and the Lower East Side in Manhattan, but they were carefully observed by education activists around the city.

The community control districts came into conflict with the United Federation of Teachers - New York’s teachers union - over the question of what role local districts would have in hiring, and potentially firing, teachers. Like other unions, one of the UFT’s main sources of power was its ability to negotiate a single contract for all of the city’s teachers, including rules about how teachers were hired and how they could be fired. Losing control of these decisions would weaken the union and make teachers feel less secure in their jobs.

But community control advocates felt this authority to hire and fire needed to be in their hands - especially because they were concerned about the racism that their students experienced in classrooms led by UFT members, who were primarily white. In the 1960s and 1970s, when Black and Latinx students became the majority in NYC public schools, fewer than one fifth of the city’s teachers were Black or Latinx. In the 1970s, there were only 5 Black principals, and no Puerto Rican principals, in the city’s 600 elementary schools.2

This conflict over teacher hiring led to a citywide teachers strike that extended over several weeks in the fall of 1968. The strike made it clear that the UFT at the time - if not all of the individual teachers it represented - stood against Black and Latinx community self-determination in education.3

Alongside the controversy, educators, students, and others worked to make self-determination a reality in the schools of the community control districts. There were unique challenges and opportunities in each district. Although the community control period was short-lived, it offered examples of what Black, Latinx, and Asian American New Yorkers of the time hoped for their schools. Unfortunately, existing historical research doesn’t provide an answer to the important question of how Disabled students experienced schools in the community control districts.

-

Jonna Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012); Christopher Hayes, The Harlem Uprising: Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021); Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell, eds., Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019); Matthew Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016); Max Freedman and Mark Winston Griffith, School Colors, 2019, produced by Brooklyn Deep, podcast, https://www.schoolcolorspodcast.com/. See also: Matthew Delmont, Why Busing Failed, accessed April 10, 2024, whybusingfailed.com. ↩︎

-

Christina Collins, “Ethnically Qualified”: Race, Merit, and the Selection of Urban Teachers, 1920-1980 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Max Freedman and Mark Winston Griffith, Season 1, 2019, in School Colors, produced by Brooklyn Deep, podcast, https://www.schoolcolorspodcast.com/brooklyn; Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Daniel Hiram Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004); Charles Isaacs, Inside Ocean Hill Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education 1968-69 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2014). ↩︎

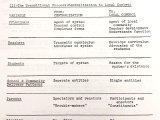

Community control demonstration districts*

1966-1970

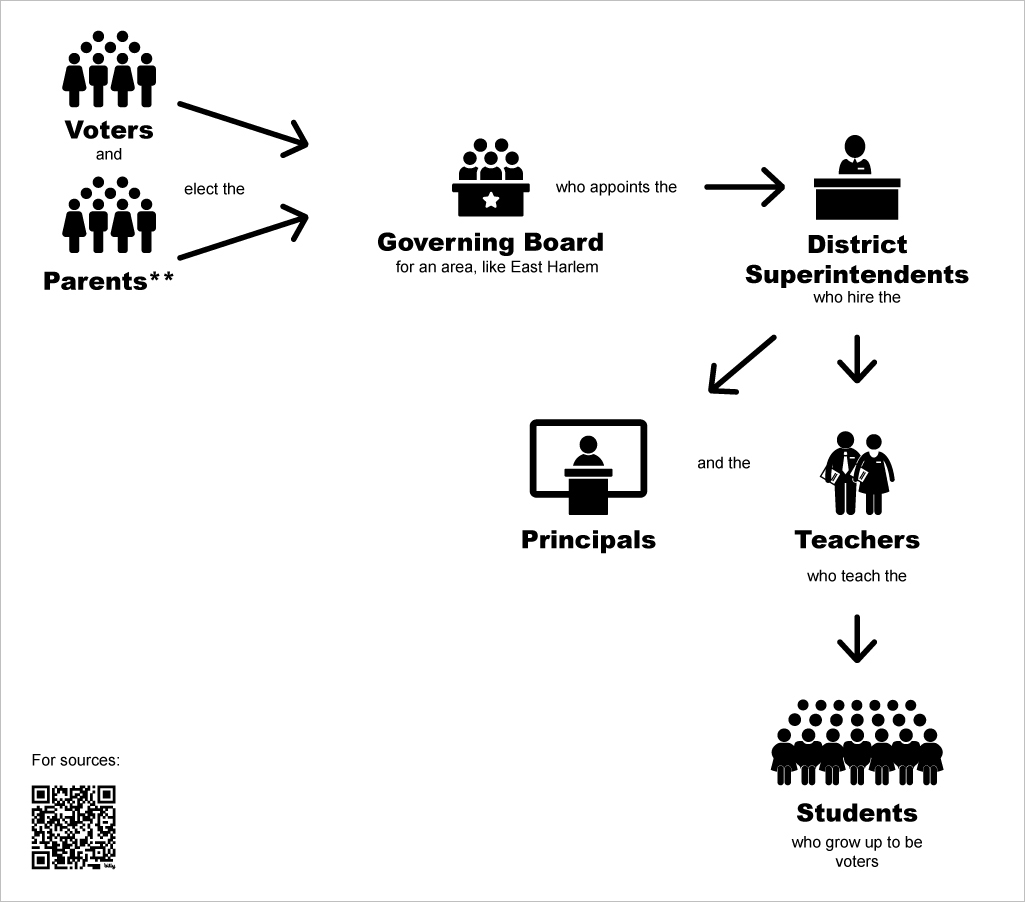

Detailed image description: This visualization focuses on who made decisions about hiring in NYC schools. Other areas, like school construction or purchasing materials for schools, may have differed. In the city’s three community control demonstration districts, parents and voters elect the members of their local district’s governing board. (Parents who were not eligible to vote in other elections could vote in school board elections). The board has authority to hire a district superintendent, principals, and teachers, who taught the students in the schools in the demonstration district.

* This slide describes the governance structure in 3 community control demonstration districts that were located in East Harlem, Ocean Hill-Brownsville, and the Lower East Side.

** Parents are included here in addition to voters because community members who were not US citizens and thus could not vote in other elections could participate in school board elections