You are here:

Decentralization: Community School Districts For Some

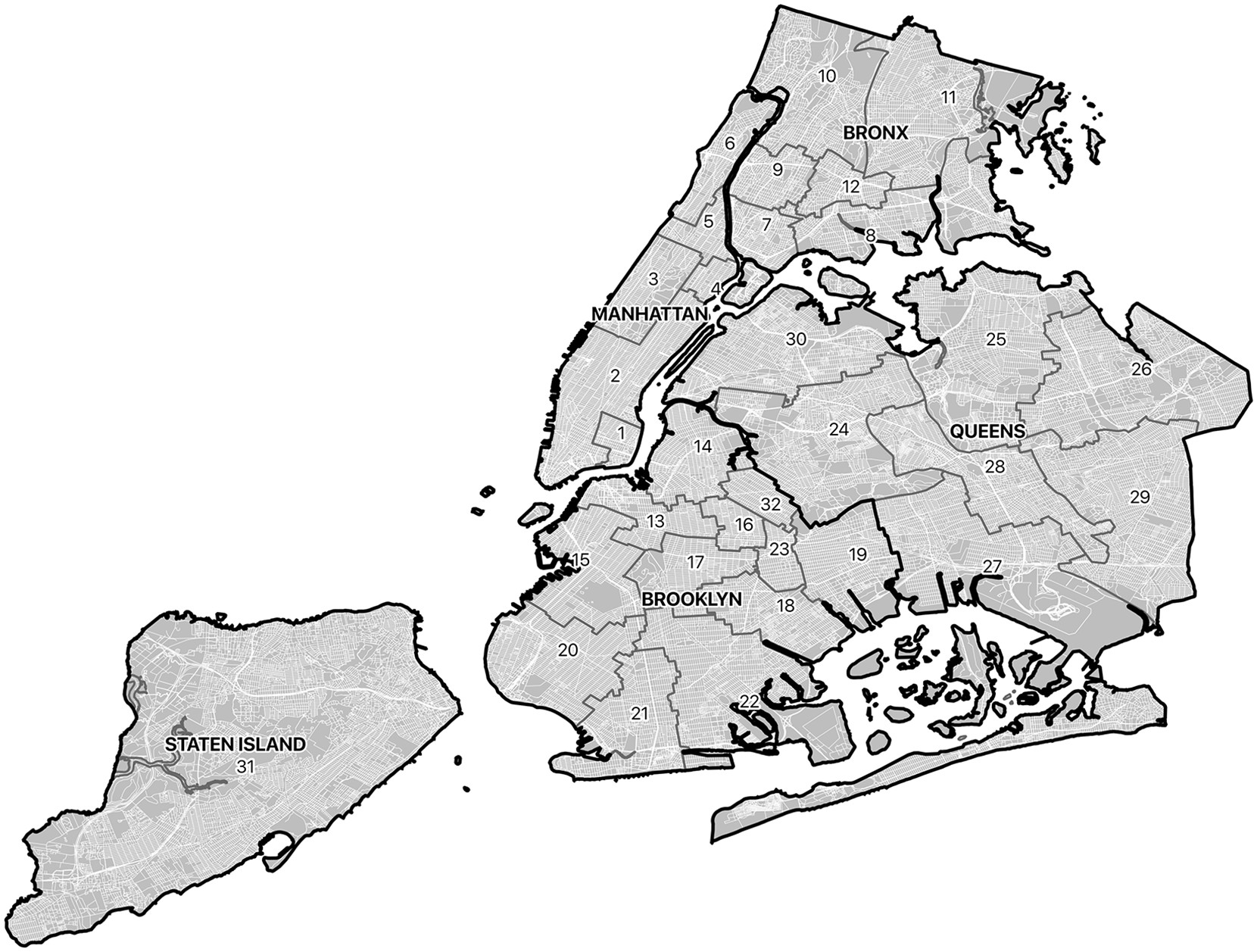

In 1969, New York’s state government passed a new law about how New York City schools would operate. The law used the term “decentralization” to describe the new plan, which would divide the city into 31 (later 32) separate “community school districts.” These district lines are still in effect today.

Read More

The decentralization law came about in part because the state government had been pushing to break up the very large New York City system into smaller (and in their view more manageable) sections for a long time. And it came about because conflict between the teachers union and community control structures left state and city officials feeling like *some* decentralization, but not [community control](/topics/who-governs-schools/community-control/), was desirable. That is, New York’s 1969 school governance plan was a compromise. It was a more decentralized system than [the centralized system in place from 1902-1969](/topics/who-governs-schools/masses-to-experts/). But decentralized community school districts had much less power than the community control districts had. Some community control advocates strongly opposed the new decentralization plan, arguing that it maintained centralized power and was very far from the educational self-determination that Black and Latinx communities had been seeking.Important new educational ideas emerged in some decentralized districts. Innovations like small schools and bilingual education flourished in decentralized districts with supportive leaders. Some district superintendents fostered major improvements in student learning.1 These ideas have continued to shape what New York’s schools look like and how they operate today.

Meanwhile, many parts of New York City’s school system were never decentralized. Some students with disabilities attended schools in their community school districts, but others were assigned separate schools in what became known as District 75. District 75 did not have a particular geographic location, unlike the community school districts. District 75 schools were all over the city, and served only Disabled students. Parents in community school districts could elect their local school board, but there was no such board for District 75.

Decentralization did not bring strong local democratic participation in school governance. Very few New Yorkers participated in community school district elections, and some district officials and community school district board members used their funds in corrupt or illegal ways. These criticisms, alongside concern about poor levels of achievement in many New York City schools, led the New York State Assembly to revisit the decentralization plan. In 1996, the legislature changed the law to remove some of the community school boards’ main powers, including the power to select and appoint the district superintendent.

It is important to note that although New York State’s legislature took action around decentralization, the legislature left in place a school funding formula that gave far less money to New York City and other urban districts in the state than it did to wealthier, whiter suburban districts. That formula was found unconstitutional by the New York State Supreme Court in 2001.2

-

Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg (New York: Teachers College Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Alliance for Quality Education, “A Brief History of CFE v. State,” accessed January 6, 2024, https://www.aqeny.org/cms_files/File/pdf/A%20Brief%20History%20of%20CFE%20v%20NYS.pdf. ↩︎

Map of Decentralized Districts

Caption: Map by Judith Kafka and Cici Matheny.

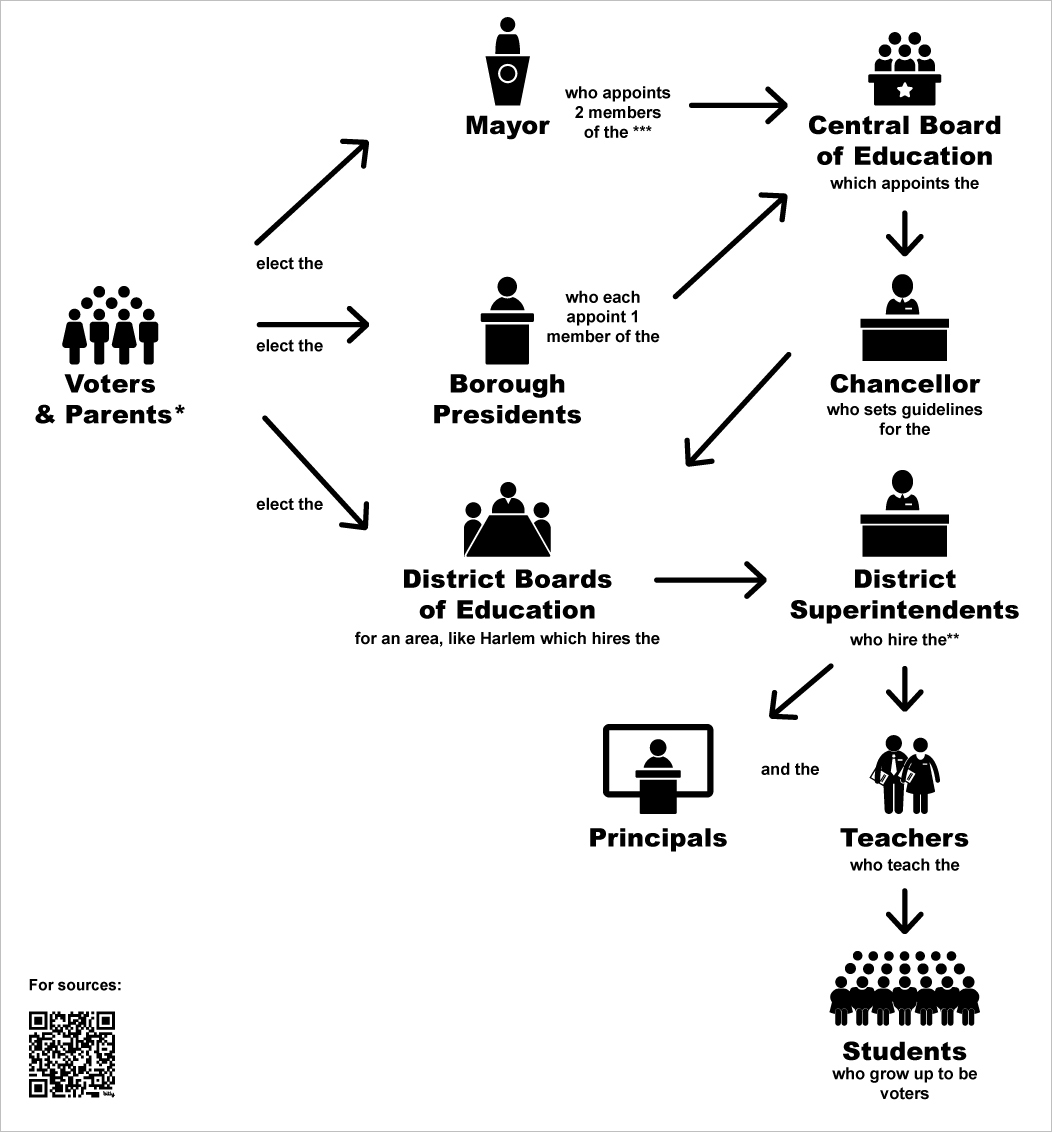

Decentralized school governance

1970-2002

Detailed image description:This visualization focuses on who made decisions about hiring in NYC schools. Other areas, like school construction or purchasing materials for schools, may have differed. A flow chart depicts a simplified version of the system, which is very complex. Under this system, voters elect the mayor, who appoints two members of the central board of education. Voters elect borough presidents, who each appoint one member of the central board of education. And voters and parents elect the members of the community school boards. (Here, parents who were not eligible to vote in other elections could vote in school board elections). The central board of education has the power to appoint the Chancellor, who then sets guidelines for the community school boards. The community school boards appoint their district’s superintendent (until 1996, when this power returned to the Chancellor). The district superintendent is in charge of hiring principals and teachers for the district, within the bounds of union contracts. These principals and teachers work in the district’s schools and teach the city’s students. The decentralized structure leaves some power in the central board of education, and moves other powers to the community school boards. High schools are not part of community school boards, and District 75 is a separate district for Disabled students under the central board.

*Parents who are not citizens can vote in board of education elections only

** Hiring is governed by rules established by the Board of Examiners (until 1990) and by union contracts.

*** This mayoral power was added in 1973. Before then, only the presidents appointed Board of Education members. From 1996-2002, this structure remained but the Chancellor hired the District Superintendents.