You are here:

From the “Masses” to “Experts”

New York’s population has often grown via immigration and migration. In the mid-1800s, the city saw large immigrant communities arrive from Ireland and Germany. In the later decades, from the 1880s onward, new waves of immigrants came from Italy, Russia, and other southern and eastern European countries. Immigrants sought relief from political and religious persecution and opportunities for employment that would help them move out of poverty. In the early 20th century, these European immigrants who would later be identified as white were joined by Black people who were immigrating from the Caribbean or migrating from the US South. Between 1870 and 1910, New York’s population grew from less than a million people to more than 4.7 million—with foreign immigration making up about 40% of the increase.1 Immigrant and migrant New Yorkers expanded the city, helped fill jobs in the growing economy, and brought large numbers of new students who needed to go to school.

Read More

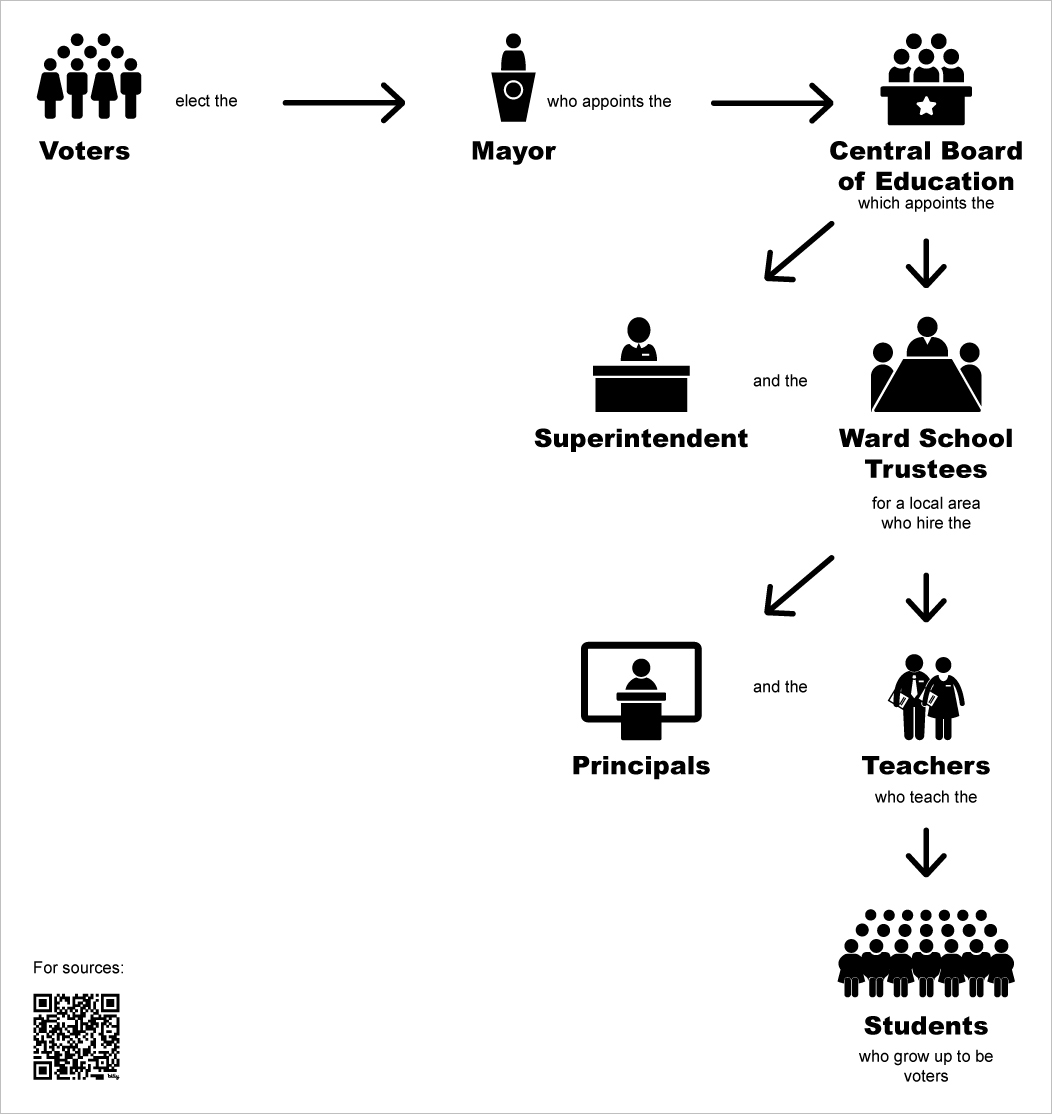

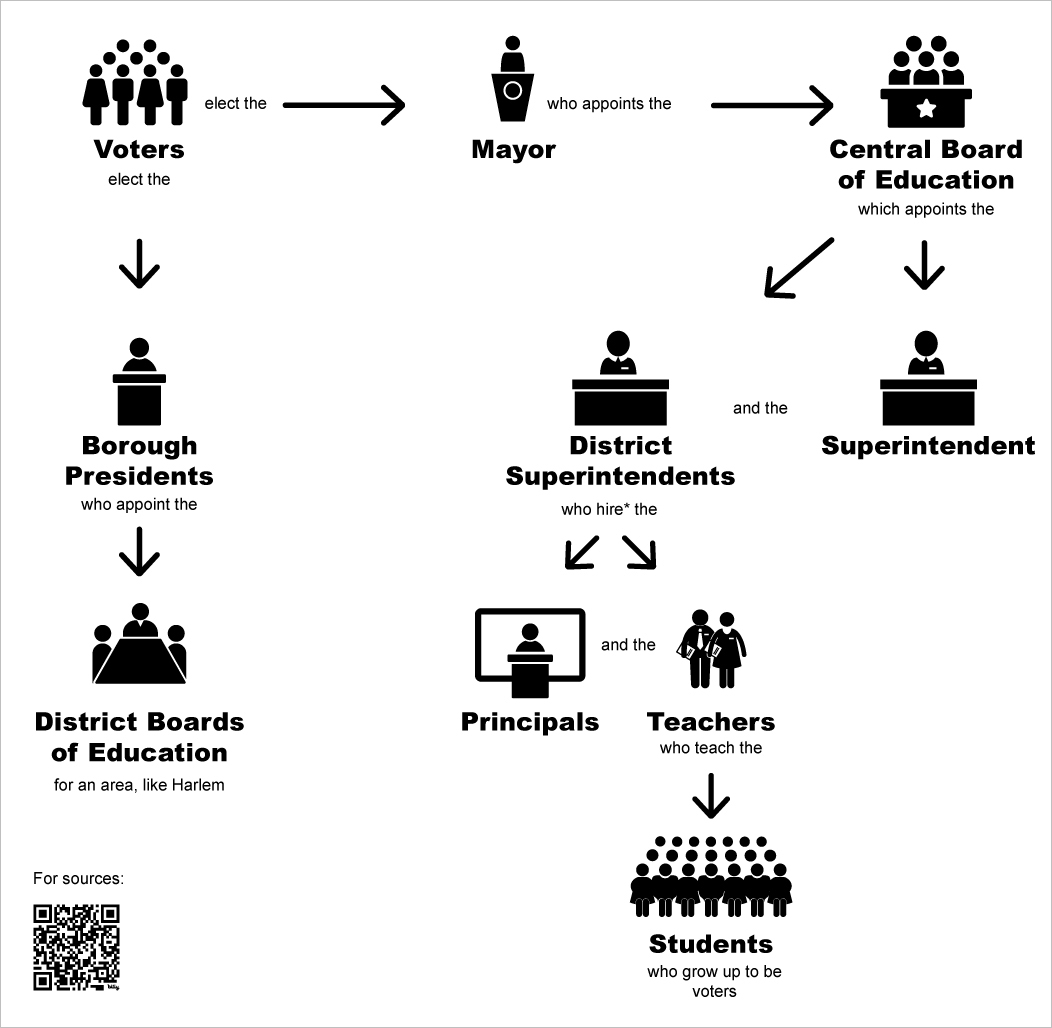

From the 1840s to the 1870s, all male New York citizens could vote for local school board members, and these boards hired teachers and principals. But should regular New Yorkers have this power? Elite white New Yorkers argued that they were the ones who held the expertise and insight to make decisions about schools — not the city’s expanding immigrant and migrant communities. They were part of a wave of “Progressive” reformers who were confident that their ideas could improve city government — in health, in housing, in schooling — for the lives of people living there.These advocates for Progressive reform, who were at the time predominantly white, Protestant Christian, and wealthy, pushed to centralize education decision-making in a new citywide school board controlled by the mayor and a board-appointed superintendent. This board would then depend on education experts to lead the school system and make schools more effective for “the masses.”2 Some elements of this system went into effect in the 1870s, and a highly centralized form of school governance was in place in New York City from 1902 to 1969.

A centralized system did not mean that all New Yorkers experienced the same opportunities at school. Because the city’s population was growing so rapidly, many schools were overcrowded. The school system built many new school buildings in neighborhoods serving growing white communities, but not in Black neighborhoods. In Harlem, for example, parents, teachers, and community advocates used several different means of protest to draw attention to conditions in their schools, and to identify how the Board of Education segregated schools by race even though New York law no longer permitted legal segregation. Black New Yorkers were frustrated by how unresponsive the centralized school system was to the needs of their children.

-

New York City, Department of City Planning, Population Division, “1790-2000 NYC Historical and Foreign Born Population,” accessed January 6, 2024, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/data-maps/nyc-population/historical-population/1790-2000_nyc_total_foreign_birth.pdf. ↩︎

-

David B. Tyack, The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), 129-146. ↩︎

Centralized school governance, part 1

1873-1896

Detailed image description: This visualization focuses on who made decisions about hiring in NYC schools. Other areas, like school construction or purchasing materials for schools, may have differed.Voters elect the mayor, who appoints the central board of education. The central board appoints a superintendent for the whole school system, and school trustees (who are like school board members) for each local district. The trustees have the power to hire principals and teachers, who lead the schools and teach the students. This model is based on Manhattan and the Bronx, whose schools consolidated in 1873. There may have been differences in school governance in Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.

Note that this model is based on Manhattan and the Bronx. More research is needed to determine if there were variations in Brooklyn, Queens, and Richmond/Staten Island.

Centralized school governance, part 2

1902-1970

Detailed image description:This visualization focuses on who made decisions about hiring in NYC schools. Other areas, like school construction or purchasing materials for schools, may have differed. Voters elect the mayor, who appoints the central board of education. The central board of education appoints district superintendents, who hired principals and teachers. Hiring was shaped in part by the city’s board of examiners, who control the process for becoming a teacher or principal until 1990. After 1961, hiring is governed by the teachers union contract. Voters also elect borough presidents, who appoint local boards of education for each district. These districts had limited power.

*Hiring is governed by rules established by the Board of Examiners and (after 1961) union contracts.