You are here:

Mayoral Control

In the 1980s and 1990s, many city school systems around the country were struggling. They did not have enough resources, and many students were not learning as much as they should have been. Some people said the problem was how schools were governed. Decentralized control had been messy, with too many people weighing in on decisions. (Often, people making this argument implied that urban residents, many of whom were working-class Black and Latinx people, couldn’t be trusted to govern their own schools). The system was inefficient, and at worst corrupt, they said.1 Some claimed that the way to fix this problem was more centralized governance, putting more power in the hands of a few leaders who would run schools more like businesses and, they thought, improve school performance.

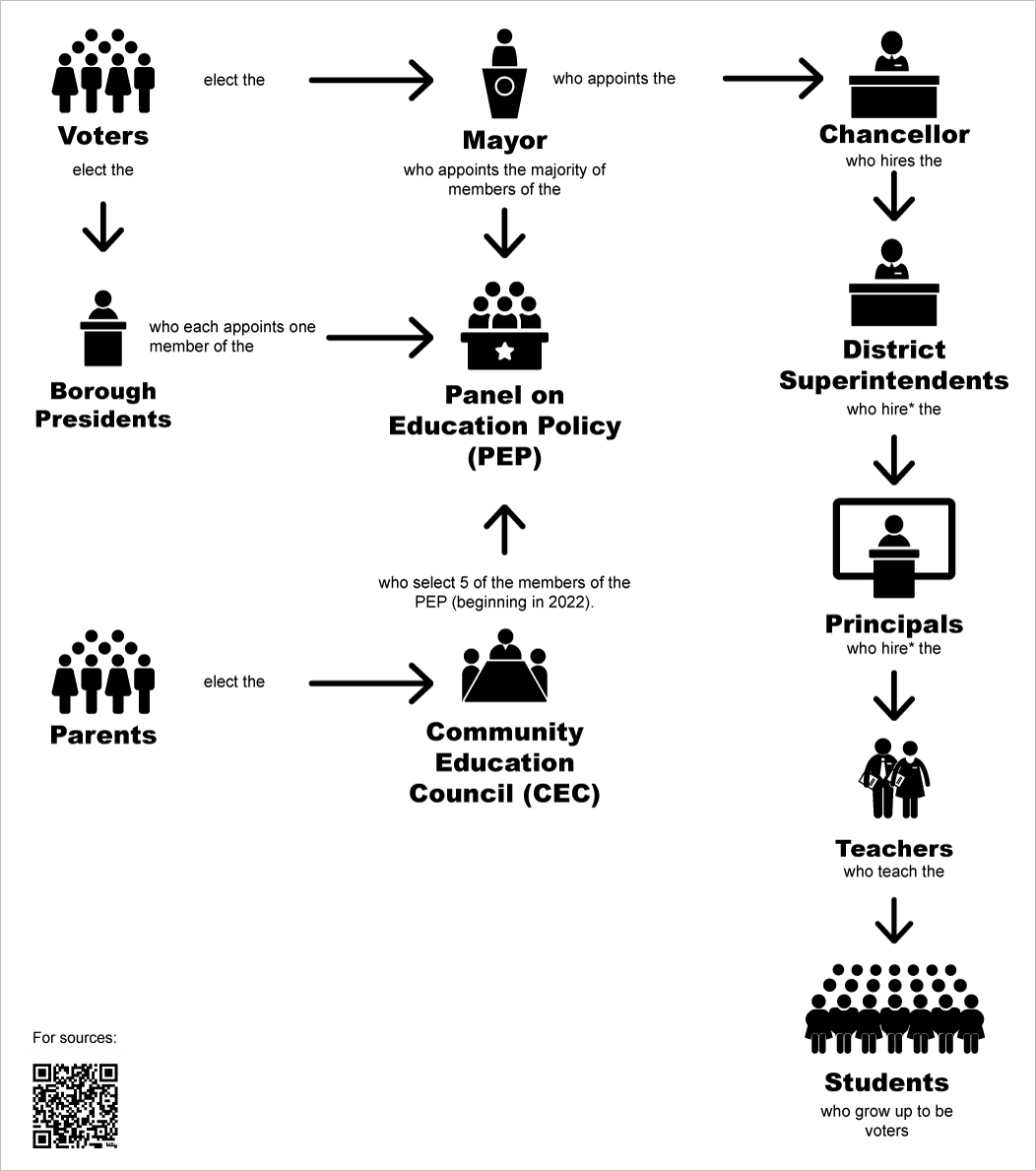

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, among others, made this argument. In 2002 he persuaded the state legislature to give him power to shape a new, very centralized, system of control of NYC schools. Voters elect the mayor, and the mayor chooses the head of the city school system and the majority of the members of the Panel on Education Policy, the body that replaced the Board of Education. There have been a few modifications since 2002, but that system remains in place today.

Read More

Domingo Morel, a political science professor, studied changes in school governance in city school systems from the 1980s until 2013. He found that predominantly Black school districts were more likely to move to mayoral control or to be taken over by state governments than districts with predominantly white student populations. Morel argues that removing or reducing local voters’ power over school systems in Black and Latinx communities has been part of a broader effort to reduce the political engagement and power of Black and Latinx communities. These communities previously have gained political power through local politics, including local school governance.2

Under mayoral control, the Chancellor and the Department of Education undertake several major changes in how New York’s schools operated. They encouraged the creation of many new small schools of choice, especially at the high school level, which students could apply to from across the city (in most cases). They also opened dozens of new charter schools, which were funded with tax dollars but were governed by private boards. The Department of Education also reorganized school districts a few times, and made pre-kindergarten available to all 3 and 4 year olds. There were many other changes to school curriculum, leadership, and budget as well.

Advocates for mayoral control say that these changes were good ones for the city’s schools and children. Charter school test scores often came in higher than those of district schools, for example. Small schools of choice helped increase NYC’s graduation rate.3 But critics point out that many of these changes had serious downsides, that deep inequality in the city system remained, and that mayoral control makes it harder for concerned parents or community members to express their concerns and win needed changes.4 They say that the same problems that can appear with local democratic governance - like corruption - also appear in a centralized system that gives the mayor and chancellor a great deal of power.

Debates over mayoral control involve concerns over principles - what is the right way to govern schools in a diverse city in a democracy? - and over outcomes - which approach has been or could be more effective at yielding the results New Yorkers’ want for their schools?

Mayoral control is not a permanent part of New York state law, but is subject to renewal every few years. In late 2023 and early 2024, New York residents are participating in a series of hearings to discuss mayoral control and its future.

-

Heather Lewis, New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy (New York: Teachers College Press, 2018), 135-138. ↩︎

-

Domingo Morel, Takeover: Race, Education, and American Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

New York City Charter School Center, “NYC Charter School Center Test Score Analysis, 2021-22,” accessed March 24, 2024, https://nyccharterschools.org/new-york-city-charter-school-center-test-score-analysis-2021-22/; Howard Bloom, Saskia Levy Thompson, and Rebecca Unterman. Transforming the High School Experience (New York: MDRC, 2010), https://www.mdrc.org/work/publications/transforming-high-school-experience. ↩︎

-

Advocates for Children, “NYC Charter Schools are Illegally Pushing Out “Difficult” Kids, Report Alleges,” accessed March 25, 2024, https://advocatesforchildren.org/articles/nyc-charter-schools-are-illegally-pushing-out-difficult-kids-report-alleges/; Alliance for Quality Education, “A Majority of NYC’s School Aid Increase Goes to Charter Schools. How?,” accessed March 25, 2024, https://www.aqeny.org/2022/01/24/2489/. ↩︎

Mayoral control of schools

2002-today

Detailed image description: This visualization focuses on who made decisions about hiring in NYC schools. Other areas, like school construction or purchasing materials for schools, may have differed.A flow chart depicts a simplified version of the system. Voters elect the mayor, has the power to appoint the chancellor and the majority of the members of the Panel on Education Policy. The Chancellor has authority over hiring district superintendents, who hire principals and teachers to teach the students. Voters elect borough presidents, who each appoint one member of the panel on education policy. Parents elect Community Education Councils. Starting in 2022, the Community Education Councils together selected five members of the Panel on Education Policy.

* Hiring is governed by union contracts.