You are here:

We Kept Our Retarded Child At Home, excerpt

Date: Nov 1, 1955

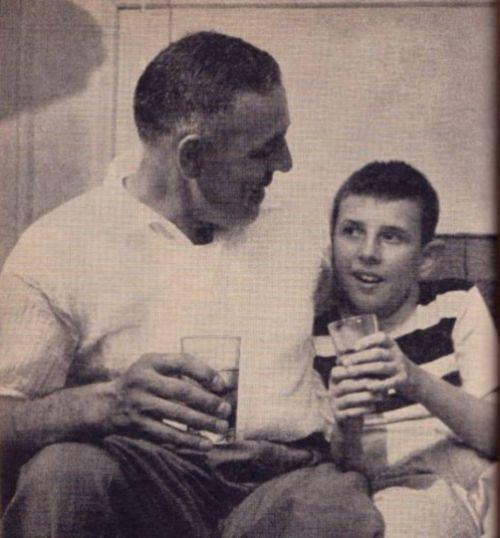

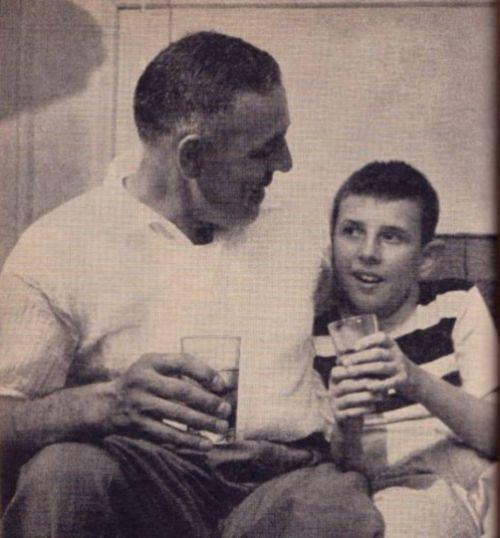

Caption: A reporter for Coronet magazine interviewed the father of a ten-year-old boy with an intellectual or developmental disability (which was referred to as mental retardation at the time). The father described the pressure to send his child Eddie to an institution and his hopes for his son.

Willowbrook opened in 1947. The number of people living at institutions in and around New York City increased in the early twentieth century as physicians frequently told parents of “mentally retarded” children to send them to institutions where they could be rehabilitated. At this time, public schools could still turn away children if they thought they were “uneducable.”1

Frank Picolla, the father, spoke to writer Ralph Bass about his son, Eddie. Picolla describes his son’s life at home, what he enjoyed and what frustrated him, and how neighbors responded to him.

Here is the complete interview.

Eddie is ten. He can’t dress himself, tell time or play “hide and seek” like other kids. But he can repay love and affection.

EIGHT YEARS AGO, when our son Eddie was two years old, doctors told us we would have to shut him up in an institution for retarded children. I usually take my time before making up my mind, but for once I didn’t wait a split second before deciding good and loud, “Over my dead body!”

We haven’t put Eddie away. And even though at ten he’s like a four-year-old, I’d say we’re as happy a family as there is in the Borough of Queens in New York City where we live. I know you’ll find that hard to believe when I tell you some of the things Eddie can’t do and the things that he needs help with – the help of my wife or myself.

I don’t think you could tell there is anything much wrong with Eddie just by looking at him. He’s about four feet six, which isn’t too small for his age. He weighs 58 pounds, about average for his build. He has nice white teeth and a straight nose. If you smile at him, he smiles right back. It’s when Eddie moves around that you notice he’s different. His wrists are kind of loose, and also, he can’t control his left leg too well. About the only other outwardly abnormal thing about Eddie is his unusual restlessness. He moves around all the time and you can’t get him to stop talking. Strangers often find it hard to follow what he’s saying, but we understand him. It’s usually something like wanting to go for a ride or asking for a drink of water – anything a very young kid might jabber about.

Sometimes it’s hard to figure out if Eddie understands everything you say to him. But there’s one thing sure: he’s sensitive and his feelings get hurt.

I think the main cause of these moments of misery is the fact that people don’t understand about kids like him. Some of our neighbors seem to think he’s a kind of monster who might do God-knows-what to their children.

About a year ago, we heard Eddie screaming and rushed out in time to see a woman give him a shove that made him stagger. It turned out that she had warned her little daughter against going anywhere near Eddie; and when the child saw Eddie she very naturally cried out in fear and her mother rushed over to “protect her.”

A little later we had a visit from a truant officer who wanted to know why Eddie wasn’t in school. It didn’t take him long to realize Anna and I would have gone down on our knees to give thanks if Eddie could go to school.

We were pretty sure we knew who had made the complaint. But we weren’t really angry because we’ve learned one thing: people hurt you more out of ignorance than malice. We just felt rotten; and Eddie, as usual, knew it had something to do with him. He went around with a sad look that haunted me.

Once, my wife was trying to get Eddie to take some glutamic acid tablets which a doctor had suggested, feeling they might help him. He hated the stuff and, like any kid, was putting up quite an objection.

The first thing we knew, a squad car pulled up. A neighbor had figured that anything Eddie was involved in needed police action, quick! And Eddie – a kid who is all love and affection for anyone who will meet him one tenth of the way.

THOUGH THERE ARE plenty of things Eddie can’t do, there are items on the credit side. For one thing, he rides a three-wheeler. It took him a year to learn. So what! He can’t play with other kids. But that brings him closer to us, and I guess we have become pretty much his whole world.

I keep thinking that in six more years I’ll get my pension and Eddie and I can spend more time together. He loves to go driving with me and he has a remarkably good memory. He’ll tell me to turn at a corner when I make believe I’ve forgotten.

Around the house he plays with a tin dish he calls his steering wheel. But as simple as that would seem to make him, he can easily recognize the cars of friends a block away.

-

Steven Noll, “Institutions for People with Disabilities in North America,” in The Oxford Handbook of Disability History, ed. Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick, and Kim E. Nielsen, Oxford Handbooks (2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 10 July 2018), accessed April 21, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190234959.013.19. Thanks to Francine Almash for the citation. ↩︎

Categories: Staten Island, parent activism

Tags: racist segregation, institutionalization of Disabled people and people labeled disabled, Disabled people, intellectual disabilities, white people, social and economic class, employment, exclusion from schooling

This item is part of "Willie Mae Goodman fighting Willowbrook" in "Black and Latina Women’s Educational Activism"

Item Details

Date: Nov 1, 1955

Creator: Frank Piccola, as told to Ralph Bass

Source: Coronet Magazine and the Disability History Museum

Copyright: Under copyright. Used with permission.

How to cite: “We Kept Our Retarded Child At Home, excerpt,” Frank Piccola, as told to Ralph Bass, in New York City Civil Rights History Project, Accessed: [Month Day, Year], https://nyccivilrightshistory.org/gallery/we-kept-our-child-at-home.

Questions to Consider

- What did Eddie enjoy doing at home and with his family?

- What challenges did Eddie and his family face in his neighborhood and community?

- What conditions made it possible for Eddie’s family to decide not to send him to an institution, as a doctor suggested, and instead to support him in living at home?

References

How to Print this Page

- Press Ctrl + P or Cmd + P to open the print dialogue window.

- Under settings, choose "display headers and footers" if you want to print page numbers and the web address.

- Embedded PDF files will not print as part of the page. For best printing results, download the PDF and print from Adobe Reader or Preview.