Boycotting New York’s Segregated Schools

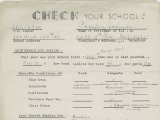

In 1964, New York’s schools were highly segregated and unequal. It was ten years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision that declared school segregation to be unconstitutional. But despite a decade of protests, rallies, and meetings, little had changed in New York City classrooms. If anything, schools had grown more segregated and unequal. Segregation in housing and employment contributed to school segregation. Yet many decisions made by the Board of Education helped segregate New York City’s schools as well: which students were zoned or assigned to which schools, where schools were built or not built, which teachers worked at which schools, and how students were grouped or divided within classrooms and schools.

Read More

Segregation came with and worsened educational inequality. New York schools with more Black and Latinx students were more likely to be overcrowded, to have less-qualified teachers, to have poor facilities, and to see fewer students graduate, for example.1

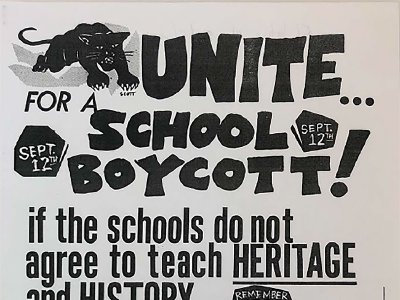

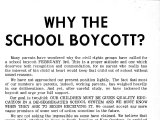

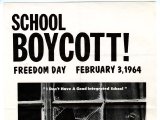

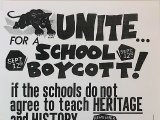

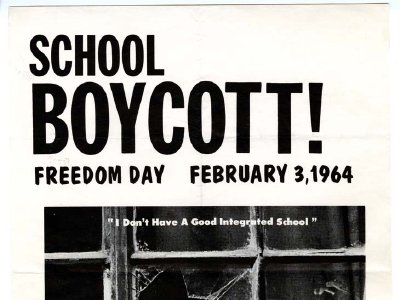

New Yorkers seeking educational justice used school boycotts as a way to protest segregation and the inequality that came with it. During boycotts, students chose not to attend school, or parents kept their children home. Some activists organized alternative “freedom schools” for children. Mae Mallory and the “Harlem Nine” had used this tactic in 1958, to protest segregation in Harlem schools. But on February 3, 1964, a massive boycott reached across the city. An estimated 464,000 young people - roughly half of New York City’s public school students, including many Black, Latinx, and white students - boycotted school in protest of segregation and inequality. At that time, it was the largest mass protest ever conducted in the United States.2 The boycotts continued, on a smaller scale, in March 1964 and January 1965, and they prompted major counter-protests as well.

Given how many students from across New York City participated in the February 3, 1964 “Freedom Day” boycott, it is likely that students with disabilities were part of the protest. It may also be the case that some who wanted to participate did not have access. The existing documentation of that boycott makes it hard to be sure.

Despite the massive scale of the February 1964 boycott, and the repeated use of this kind of protest in schools in New York City and around the country, the New York City school boycotts often get left out of histories of the US civil rights movement. The history of the boycotts teaches us how Black and Latinx young people and adults, and white people in solidarity with them, struggled for educational justice in the North.

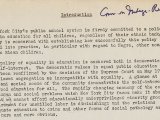

And it shows us how white opposition to desegregation worked in New York City, both among “conservative” white parents and those who thought of themselves as “liberal.”3 Even though the 1964 boycott was massive, in many ways the white counter-protesters won. Policymakers continued to defer to white citizen’s opposition to desegregation, and elected officials protected the North from some legal requirements to desegregate. Racism and segregation were national, not only southern, problems. See Key Concept #10

Historians like Jeanne Theoharis and Matt Delmont, and teachers like Adam Sanchez, have helped bring more attention to the largest 1964 New York City boycott.4 Yet in their work, there is little discussion of another boycott - the 1965 boycott, which focused in part on how Disabled youth, or youth that the school system labeled as disabled, experienced racist and ableist segregation. Historian Francine Almash is working to correct that silence. She studies the 1965 boycott, and notices how the white press, Black community members and organizers, and white educators responded when disability was part of fighting segregation. Why did so many resist including disability and students labeled as disabled in their desegregation advocacy? And she asks why earlier histories of the boycotts have left out this important part of the story.5

After the boycotts of 1964 and 1965, students, parents, and activists continued to use boycotts as one tool to protest educational injustice in New York City. The patterns of racist and ableist inequality that sparked the boycotts continue in many forms today.

-

Christopher Bonastia, The Battle Nearer to Home: The Persistence of School Segregation in New York City (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2022). ↩︎

-

It remained the largest mass demonstration until it was exceeded by the Women’s March on January 21, 2017. Matthew Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016); Jeanne Theoharis, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018). See also: Matthew Delmont, Why Busing Failed, accessed April 10, 2024, whybusingfailed.com. ↩︎

-

Theoharis, A More Beautiful and Terrible History; Delmont, Why Busing Failed; Adam Sanchez, “The Largest Civil Rights Protest You’ve Never Heard Of: Teaching the 1964 New York City Boycott,” Rethinking Schools 32, no. 4 (Winter 2019-2020),https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/the-largest-civil-rights-protest-you-ve-never-heard-of ↩︎

-

Francine Almash, “Out of the Shadows: Recovering the History of the New York City ‘600’ Schools” (Ph.D. diss., CUNY Graduate Center, in progress). ↩︎

-

John Cuscera with Gary Orfield, “New York State’s Extreme School Segregation: Inequality, Inaction, and a Damaged Future” (Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Civil Rights/Proyecto Derechos Civiles, 2014), https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/ny-norflet-report-placeholder/Kucsera-New-York-Extreme-Segregation-2014.pdf; Cheri Fancsali, “Special Education in New York City: Understanding the Landscape” (New York: Research Alliance for NYC Schools at NYU Steinhardt, 2019), https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/research-alliance/research/publications/special-education-new-york-city ↩︎

The 1964 Boycotts

A decade after Brown v. Board of Education, 500,000 New York City students boycotted schools in one of the largest mass demonstrations in U.S. history.

View primary sources

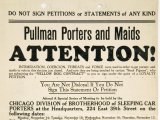

Before the Boycotts: Organizing and Direct Action

The networks, strategies, and knowledge that earlier organizers cultivated helped make the New York City school boycotts possible.

View primary sources

Before the Boycotts: Youth Organizing in New York City

To understand how a school boycott happened, it is necessary to recognize the longer history of student activism.

View primary sources

Before the Boycotts: White Resistance to Desegregation

White New Yorkers were relentless in opposing desegregation. Even very small-scale attempts by the Board of Education to desegregate schools prompted protests and backlash.

View primary sources

Responding to the 1964 Boycotts

After the boycotts, many observers commented on whether the boycotts had been successful or a good idea.

View primary sourcesNY State ends legal school segregation

New York State makes it illegal for its school districts to divide Black and white students into separate schools.

NAACP Forms Youth Councils

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) forms a youth council at various local branches, including New York City.

Planned March on Washington

A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin organize a March on Washington to protest discrimination in defense industries during World War II. Randolph and Rustin called off the march after President Roosevelt signed an executive order barring discrimination in defense industries.

Brown v. Board of Education

Supreme Court rules segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education.

Harlem Nine Boycott

Harlem Nine, nine mothers of children in schools in Harlem, boycott their children’s schools because they are segregated and unequal. The city attempts to incarcerate the Harlem Nine for their activism.

Parents’ Workshop for Equality

Parents’ Workshop for Equality is founded by Reverend Milton Galamison.

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

More than 200,000 people congregated in Washington, DC in support of civil rights and full employment.

“Freedom Day” School Boycott

An estimated 464,000 young people - roughly half of New York City’s public school students - boycott their school in protest of segregation and inequality

Second School Boycott

A second boycott draws fewer participants than the “Freedom Day” boycott.

“Harlem Six” arrested

“Harlem Six” teens arrested and accused of participating in a “Fruit Riot” and, later, in a murder.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

President Lyndon Johnson signs into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The landmark legislation prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. However, northern legislators in Congress ensured that the legislation would not upend segregation in the North.

“Operation Shutdown” organizing begins

“Operation Shutdown” organizing begins, led by Reverend Milton Galamison.

Operation Shut Down ends

Reverend Milton Galamison ends Operation Shutdown.