Joyful Struggle

When you imagine a movement or a protest, what do you see? What are people doing? What kinds of activities are they involved in?

Do the images in your mind include expressions of joy, moments of beauty, places for play?

These primary sources explore the topic of joyful struggle. First they show joy, play, pride, and beauty in Black and Latinx communities and in Disabled people’s communities. Too many historic representations of people of color and Disabled people only pay attention to what is difficult, hard, or painful.1 But these and other historically marginalized communities have also nurtured joy, love, and beauty in their own ways. Sharing joy could be one way to heal and affirm, to reinforce and build strength and community in the face of harsh or even violent treatment due to racism and ableism.2

Read More

Secondly, these sources help us think about how joy can be political—that is, how it can be connected to and can even be a method of working to make change. Joy, beauty, and play are important parts of self-expression and self-determination. Black communities celebrated and reinforced their ways of knowing and being through expressions of joy, even when others did not see them as they wanted to be seen.3 Disabled communities created spaces for connection and celebration of disability.4 Joyful spaces that communities built for themselves countered what was wrong or lacking in other oppressive or exclusionary spaces. They gave Disabled people and Black and Latinx people opportunities to imagine new possibilities. And they nourished the strength and community ties that made other political movements possible.

For many people, ideas about childhood and joy go together. But not all children have been able to enjoy the joyful childhood they deserved, in part because of the consequences of racism and ableism. These primary source documents help us see times when young people and adults worked to create spaces for joy, beauty, and play in children’s lives—and how these spaces have been linked to children’s and adults’ sense of their own power to make change in the world.

Many scholars and educators are pointing out this pattern. For a good summary of the problem and ways to respond in teaching Black history, see Jania Hoover, “Don’t Teach Black History Without Joy,” Education Week, February 19, 2021, accessed July 5, 2023, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-dont-teach-black-history-without-joy/2021/02. ↩︎

For example, see Crip Camp, directed by James Lebrecht and Nicole Newnham (2020: James Lebrecht, Nicole Newnham, and Sara Bolder), netflix.com; Renata Cherlise, Black Archives: A Photographic Celebration of Black Life (New York: Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed, 2023). ↩︎

Elaine Nichols, “Black Joy: Resistance, Resilience, and Reclamation,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, accessed July 5, 2023, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/black-joy-resistance-resilience-and-reclamation. ↩︎

Crip Camp, directed by Newnham and LeBrecht. See also s. e. smith, “The Beauty of Spaces Created For and By Disabled People,” An Unquiet Mind, Catapult, October 22, 2018, https://catapult.co/stories/the-beauty-of-spaces-created-for-and-by-disabled-people ↩︎

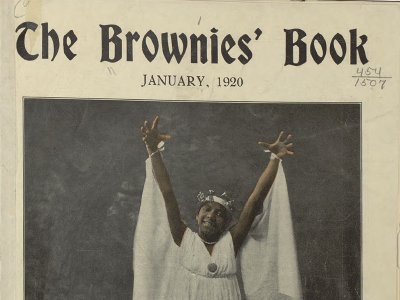

The Brownies’ Book

The NAACP published The Brownies’ Book magazine to teach Black children the history, achievements, and beauty of Black people in the United States.

View primary sources

Benjamin Franklin High School

New programs support East Harlem’s immigrant and migrant communities.

View primary sources

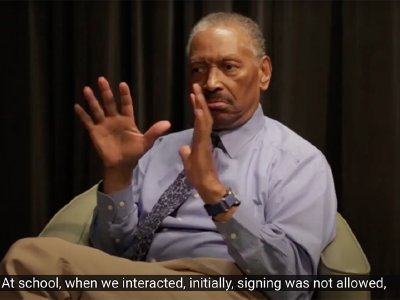

Deaf Social Spaces

When sign language was banned in schools, Deaf students found a social space to communicate freely.

View primary sources