Who Governs Schools?

Maybe the most important question in education is: who decides? Choices about what students learn, who attends school where, who teaches: the lives of more than a million students in NYC are shaped by these kinds of decisions each day. New York City and state officials are today debating who makes decisions about New York City schools and how. The history of these debates can help inform our choices in the present.

Read More

In many places outside of the US, educational policy decisions are made by the national government, but states and local school districts in the US have more power in education decisions. Small and medium-sized school districts often have elected school boards; bigger city districts, like New York, take a variety of different approaches, and they have changed a great deal over time. New York State plays a role in these changes, because state law establishes and governs local school districts.School governance in New York City has been like a pendulum, swinging between more centralized systems on one side and more decentralized systems on the other, and back again. Centralized governance —- like the current mayoral control system— - means that most decisions are made by the school system leadership for the whole system, and a lot of power is in a few people’s hands. By contrast, decentralized governance means that some or many important decisions are made in local communities, and a broader number of people are involved in making decisions. Shifts from centralized to decentralized governance have not always meant the same thing to all students. Disabled students in New York City, for example, have experienced more centralized control of their schooling, even during periods of decentralization.

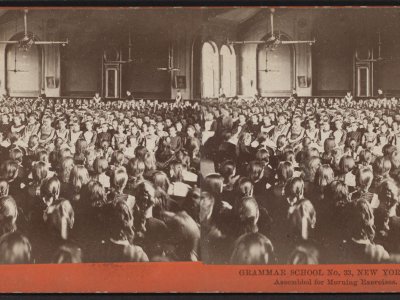

New York City’s public school system—established in 1842—started as a very decentralized system. Voters and officials in small local wards had a lot of power over their local schools. Starting in the 1870s, the system became more centralized, as it remained through the 1960s.1

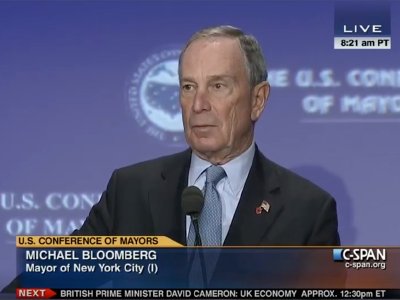

In the 1960s, parents and community leaders in a few NYC neighborhoods pushed hard to get more power in their own hands, allowing them to make more decisions about schools serving their children.2 That effort helped prompt a new wave of decentralized governance that was in place until 2002, when the current system of mayoral control began. Today, the mayor has a great deal of power over the city’s school system, as he selects the chancellor and controls the majority of seats on the city’s Panel on Education Policy.

This collection explores how, over different periods of time, people have advocated for changes in how New York City governs its schools. It focuses especially on people who argued for change in the system, to understand their arguments and their hopes for new systems of governance. Discussions of school governance were always related to the context of the system at the time: who the students were, where they lived and where they went to school, and how fairly, or unfairly, the school system served students in different communities. School governance debates connected to many civil rights and educational justice struggles, and often reflected racist and xenophobic ideas as well as efforts to challenge them. In both the past and the present, white politicians and education reformers have turned to racist ideas in their arguments about how schools should be governed. Meanwhile Black, Latinx, Indigenous peoples, and immigrant communities of various racial backgrounds have combated these ideas and provided their own alternate visions.

-

Diane Ravitch, The Great School Wars: A History of the New York Public Schools (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974). ↩︎

-

Max Freedman and Mark Winston Griffith, Season 1, 2019, in School Colors, produced by Brooklyn Deep, podcast, https://www.schoolcolorspodcast.com/brooklyn; Jerald E. Podair, The Strike that Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Daniel Hiram Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004); Charles Isaacs, Inside Ocean Hill Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education 1968-69 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2014). ↩︎

From the “Masses” to “Experts”

Progressive elites claim power to govern in a growing and diverse city.

View primary sources

The Push for Community Control

Frustrated with segregation and inequality, Black and Latinx parents push for community control.

View primary sources